ISRP Newsletter – Issue No. 2

In this issue

- Russia’s Illegal annexation of parts of Ukrainian Crimea is met with widespread rejection from the international community – and a fresh set of U.S. sanctions.

- The European Union is expected to ban Russian exports of semi-finished steel at long last – a critical decision in efforts to hold Russia accountable.

- There is plenty of room for further sanctions expansion – especially against owners of companies that are shipping stolen Ukrainian resources, among others.

- Putin calls the program for humanitarian grain shipments “hype” and claims that Europeans are the principal beneficiaries, but the facts show otherwise.

- It is not just grain and other agricultural products being looted. Steel and industrial equipment are targeted by Russian piracy as well.

- Wanted: accomplices to move stolen Ukrainian asset.

Russia’s Illegal annexation

On September 30, Russia announced an illegal annexation of territories comprising about one-seventh of Ukraine: Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. One consequence could be – and should be – a ban by the European Union of imports of semi-finished steel from Russia. As retired Ambassador James K. Glassman, chief spokesperson for the Initiative for the Study of Russian Piracy (ISRP), stated in a press release on Aug. 30:

“What would really help is a full-on ban of all Russian steel products, not just by the EU but by countries such as Turkey. By purchasing Russian steel, these nations are aiding in Russia’s war on Ukraine – and prolonging the terrible suffering.”

The Response to Illegal Annexation

Russia’s absurd claim of annexation was immediately rejected by President Biden, the United Nations Secretary General, the Prime Ministers of Japan and Britain, European Union officials and other world leaders.

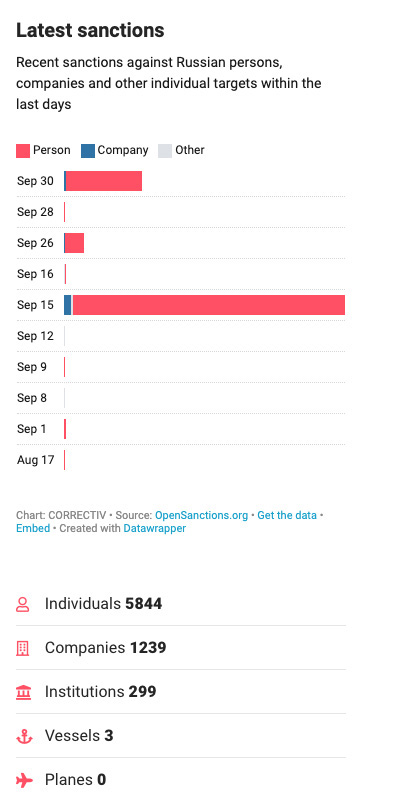

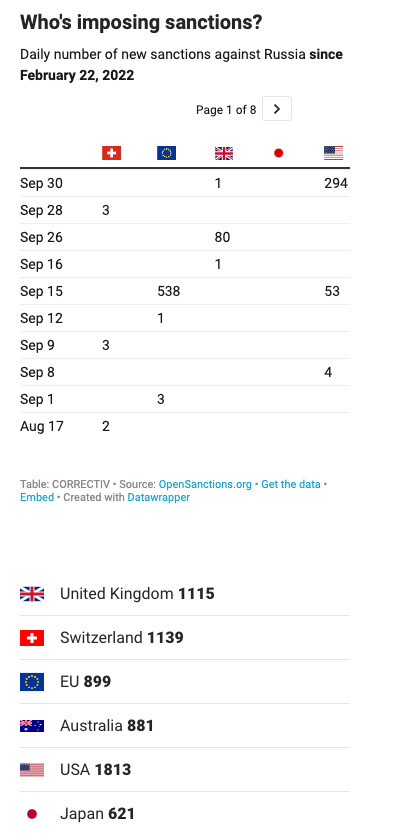

Also in response, the U.S. Administration said it was imposing “swift and severe costs” on Russia, including sanctions “targeting additional Russian government officials and leaders, their family members, Russian and Belarusian military officials, and defense procurement networks, including international suppliers supporting Russia’s military-industrial complex.”

U.S. actions combine export controls, visa restrictions and asset freezes. Targets are supply chains and individuals, among them, Elvira Nabiullina, an economist who has headed Russia’s central bank since 2013. As CNBC put it, “The newly sanctioned entities include shell companies formed specifically to evade previous sanctions.” The fact that the new sanctions include wives and children is “a sign that officials believe the family sanctions are having an impact.”

The EU is preparing its own sanctions package, which could be even more significant. According to the Wall Street Journal, it “includes a full import ban on steel and steel products from Russia, as well as bans on paper, machinery and appliances, chemicals, plastics, and Russian cigarettes imports.”

The steel import ban is critical. As the ISRP pointed out in its Aug. 30 press release, “Three weeks after the invasion of Ukraine, the European Union banned imports of Russian finished steel products, but the EU permits imports of semi-finished products, such as slab and cast iron.”

Before the Russian invasion, Ukraine and Russia together supplied four-fifths of the semi-finished steel imported by Europe – used to manufacture such products as sheet, wire rod and pipes. After the siege of Mariupol (now part of the territory that Russia claims to have annexed) destroying the Azovstal and Ilyich Iron and Steel Works, and blocking the ports of Ukraine, the Russian Federation effectively eliminated Ukraine as a competitor in the market for metallurgic products.

If the EU moves ahead on the new sanctions regime, it is likely that semi-finished steel imports will be banned.

That decision is especially important in light of the ISRP’s recent research, which has uncovered evidence that Russia is likely stealing advanced equipment from Ukrainian steel plants in Mariupol and shipping it to largely antiquated Russian plants to help produce better-quality semi-finished steel for export or use in Russia, including in the war effort.

Sanctions currently prevent Russia from acquiring such equipment from the EU and the US. Back in April, Vladimir Putin signaled that improving steel production was a high priority. “We must make changes to the structure of production and the supply of Russian metallurgical products,” he said, calling for an expansion in industrial capability and the range of products Russia produces.

Time to Expand Sanctions Further

While the expanded sanctions are welcome, the U.S. and EU could go farther. A Reuters article on Sept. 29, explained that “the United States could still impose sanctions on Russian oligarchs and others who have not yet been targeted, experts said.” Glassman, a former State Department official, has urged that sanctions be applied to shipping companies, other firms and their managers and owners involved in the theft of Ukrainian assets, including grain and steel.

The Truth About Humanitarian Grain Shipments

The agreement to provide humanitarian shipments of grain from Ukrainian ports without Russian interference seems to be working better than anyone expected, much to the chagrin of Vladimir Putin.

Putin and Turkey’s leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, one of the authors of the plan, have claimed that the deal guaranteeing ships safe passage has not benefited developing nations, saying that,instead, grain was being sent overwhelmingly to Europe. Putin derided the arrangement, overseen by the United Nations, as “hype” and has threatened to pull out – i.e., resume military operations targeting Ukrainian ports.

However, as Alexandra Prokopenko of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has pointed out, “Putin himself acknowledged [that] neither of the two documents Russia signed to enable the export of Ukrainian grain specified any destinations, belying the Kremlin’s apparent concern over the food situation in the world’s poorest countries.”

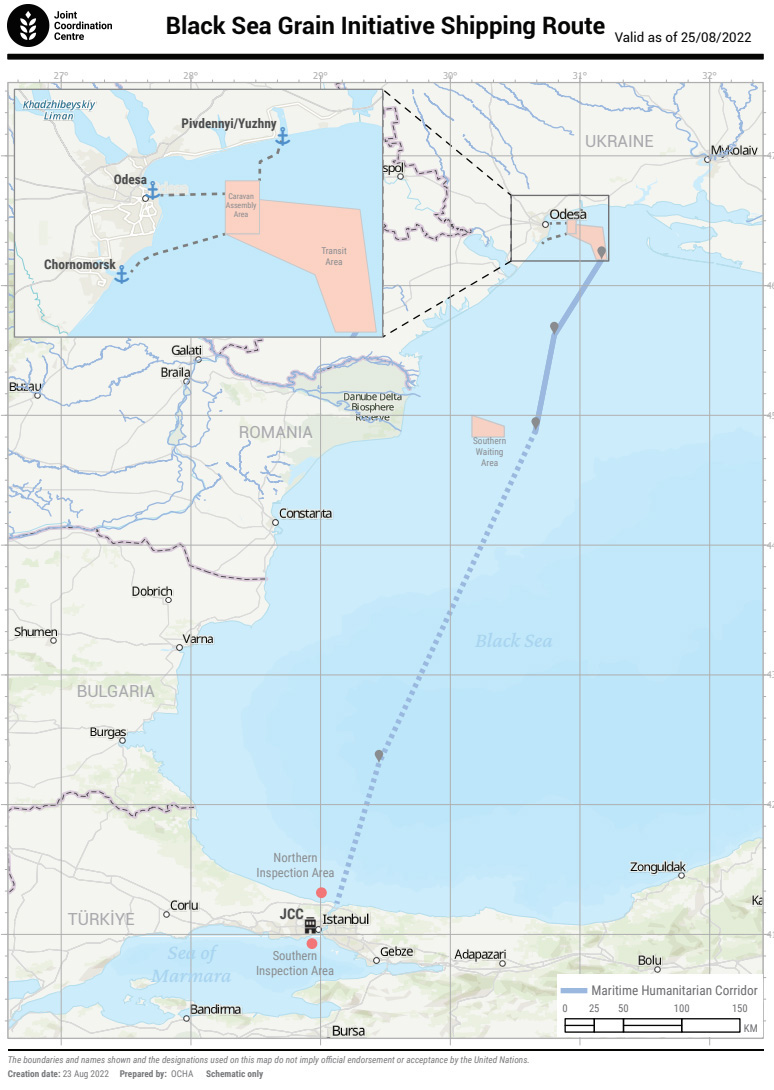

More important, Putin’s claims are simply inaccurate. The U.N. lists 241 departures of ships from the Ukrainian industrial ports of Odesa, Chernomorsk, and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi under the program between Aug. 1 and Sept. 30. Of these, 117 went to European ports, the rest to a wide variety of developing nations, including Egypt, Sudan, Iran, Kenya, China, Libya, Bangladesh, Somalia, Malaysia, India, Yemen, and Turkey itself, which has received the plurality of shipments. Notably, Turkey has also benefited greatly from the ongoing smuggling of stolen and/or sanctioned Ukrainian grain.

An analysis of data collected by Bloomberg on Sept. 8 shows that of the first 2.34 million tons of grain shipped, 36% went to Europe and 20% to Turkey while 43% went to Africa, Asia and the Middle East (the final 1% had unknown destinations).

Most of the vessels in the program are departing from the Ukrainian ports of Odessa or nearby Chornomorsk, both on the Black Sea. According to the U.N., the ships are carrying corn, wheat, soybeans, sunflower products, barley, peas, and rapeseed.

The Carnegie Endowment article noted that, because of drought in southern Europe, Ukrainian grain is in especially high demand. Prokopenko wrote:

“Soon after the deal was signed, Ukraine’s grain exports were almost back to their prewar pace. In September, Kyiv is expected to export about 4 million tons, according to Andriy Sizov, head of the SovEcon analysis center.”

Still, this figure is 2 to 3 million tons behind pre-war exports for the month, and Ukraine has an enormous amount of catching up to do. Before the corridor was opened, only about 1 to 1.5 million tons were being exported monthly.

As the shipments under U.N. supervision continue, Russia is still looting Ukrainian grain and sending it to Syria, Turkey, and elsewhere, as the ISRP and other analysts have disclosed.

The sale of this stolen grain is making up for Russian export losses from sanctions. According to the Carnegie Endowment, grain shipments from Russian ports “fell by 22 percent in July and August to 6.3 million tons. Although food supplies are exempt from Western sanctions in the interests of combating food insecurity, bankers and insurers are wary of doing business with Russia, while shipping lines are reluctant to risk sending their vessels into a conflict zone.”

Steel Being Looted from Mariupol Plants

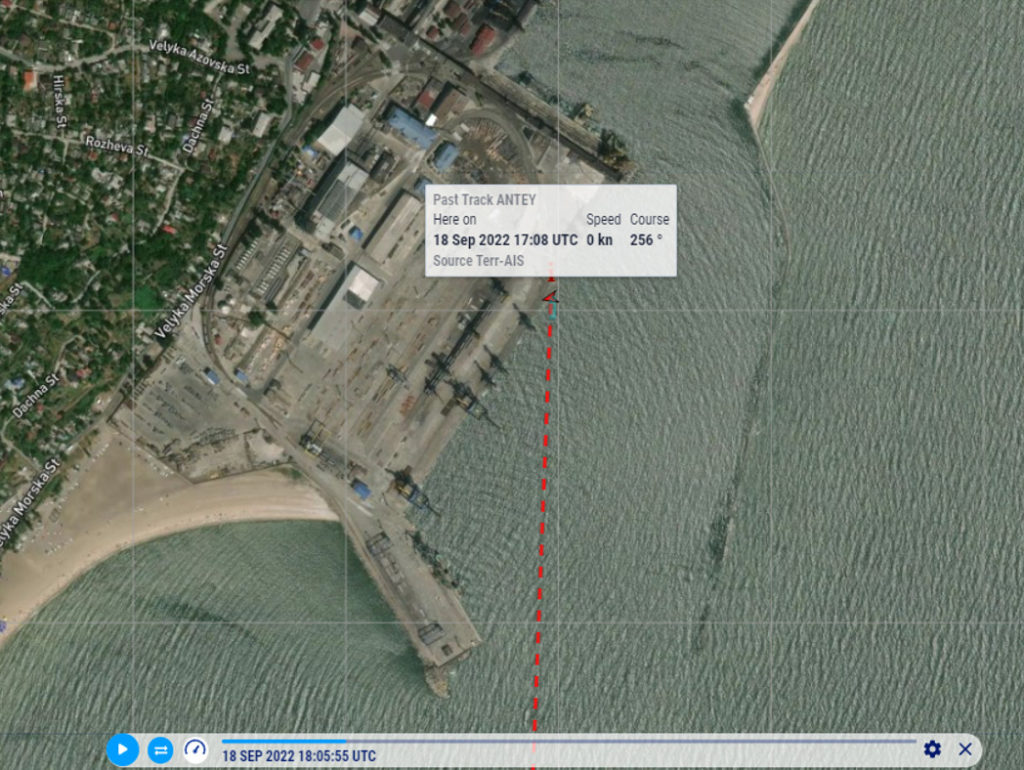

Meanwhile, the Russians are continuing to loot steel from the Mariupol plants – a further violation of international law. According to a Sept. 21 report in the Odessa Journal, a tugboat from a sanctioned shipping company arrived at the port of Mariupol from Rostov, in nearby Russia. “A vessel of this type,” said the article, “can be used to tow a barge with stolen metal that has been in the Mariupol port since the occupation.”

Antey, IMO8020147, recorded docking at berth 9 – the metal-loading berth – on September 18. It has since returned to Russia, going “dark” after reaching the industrial port of Rostov-on-Don.

According to the publication, the tugboat is owned by the Russian company Reka-More. Said the Odessa Journal: “At the end of August, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine proposed to the National Security and Defense Council to impose sanctions against the Reka-More [River Sea] Management Company and its head Gennady Arustamov.”

The RM-3, which left Mariupol carrying 2500 – 2700 tonnes of steel at the end of May, also carried its stolen cargo to Rostov-on-Don, home of Rostvertol JSC, a manufacturer of helicopters for the Russian military.

In May, Metinvest, which owns the Azovstal and Ilyich steel plants in Mariupol, issued a press release stating that a Reka-More vessel, “loaded with Ilyich Steel products, left the port of Mariupol heading towards Rostov-on-Don…. Ilyich Steel has filed a complaint with law enforcement about this criminal offense.” Ilyich also asked for “personal sanctions on Russian residents who illegally seize and resell Ukrainian metal.”

Russians Actively Advertising for Accomplices to Move Stolen Ukrainian Assets

Ship owners and operators aren’t the only ones moving stolen goods. There is a vast and sophisticated on-the-ground network that is critical to the overall effort. Drivers and other handlers are recruited through a number of means, including through social networking and chat app Telegram.

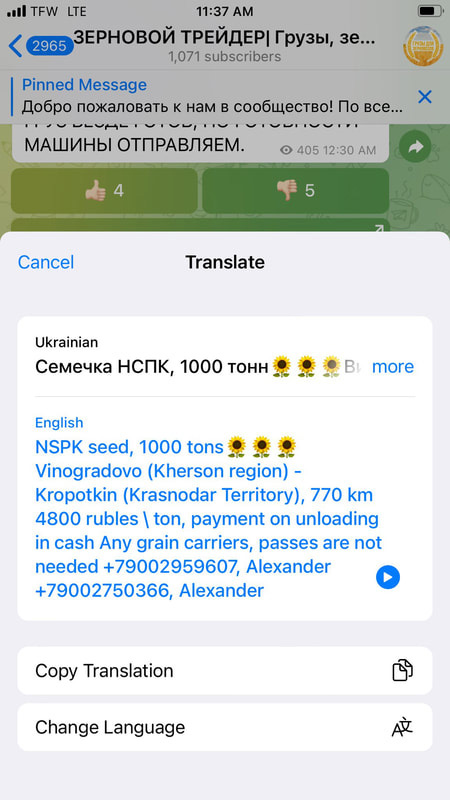

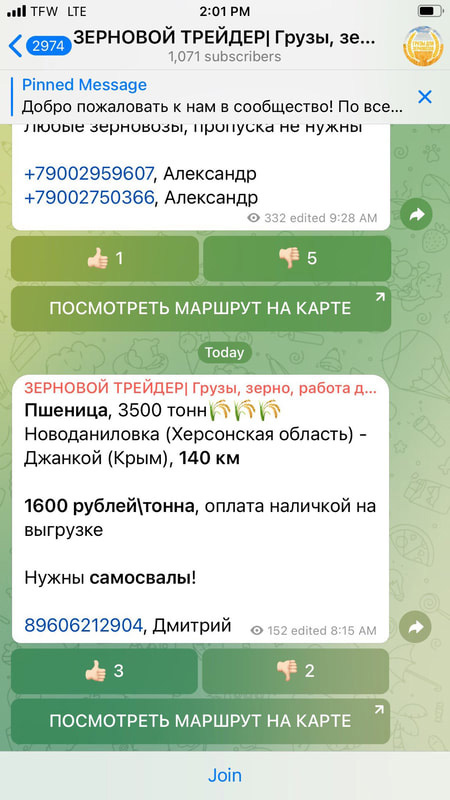

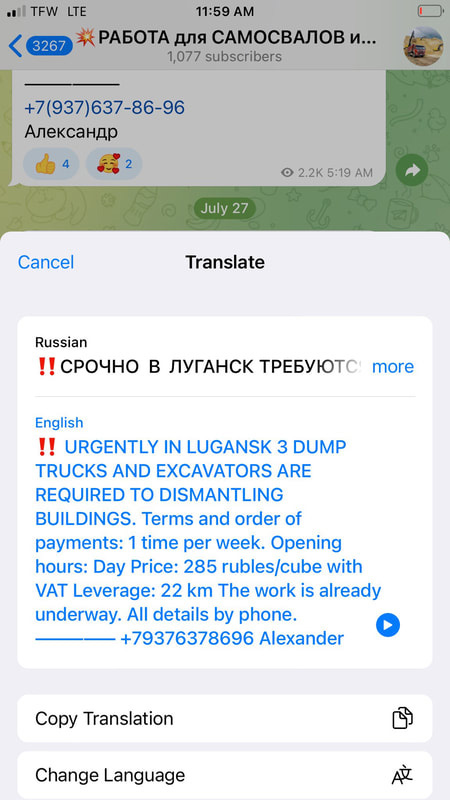

Recent posts in Russian-language Telegram channels accessed by ISRP advertise for people to help transport grain overland via personal vehicles, share routes to some of the ports where stolen grain is loaded onto ships for export, and even recruit to dismantle buildings.

More specific instructions are passed over the phone, advertisements say.

Anyone who aids in the theft of Ukrainian assets aids Russia’s war effort and prolongs the bloody conflict. As ISRP chief spokesperson Ambassador James K. Glassman said in a statement this week, “We urge the U.S. government to hold these individuals and entities accountable as well.”