Welcome to Russia Theft Watch

A message from editor, James Glassman

During its illegal invasion of Ukraine, Russia has killed at least 6,000 Ukrainian civilians and 9,000 military members, caused millions to flee or be forcibly deported to Russia, and destroyed more than $100 billion worth of infrastructure and homes. As if this brutality were not enough, Russia has also been looting resources on a historic scale, stealing hundreds of thousands of tons of grain and steel that belong to the Ukrainian people.

Whether used to feed Russian soldiers and build weapons of war, or sold by Russian entities into domestic or export markets, the stolen Ukrainian resources are prolonging the war and killing even more Ukrainians.

Recently, a group of former U.S. government officials, international trade experts, national security specialists and investigators formed the Initiative for the Study of Russian Piracy (ISRP) to track this massive theft and help media and other concerned parties tell the story to the world. This newsletter will follow the work of the ISRP as well as other researchers and reporters working on this important issue.

In this issue

- A report catalogues the Russian theft of Ukrainian assets, including grain and steel.

- How Russia loots Ukraine’s grain and sends it to ports in Turkey, Syria and other countries.

- Russia agrees to a “humanitarian corridor” to ship Ukrainian grain to a world in need — at the same time Russia is stealing that Ukrainian grain.

- Ukraine takes steps to seize ships it suspects are carrying stolen grain.

- The story of two Russian ships named Emmakris.

- In the latest example of looting, there is a high probability that valuable, sophisticated steel-making equipment is being stolen from Mariupol for use in Russia.

Initiative for the Study of Russian Piracy Issues Its First Report

On July 23, the ISRP issued an initial report on the extent of Russia’s criminal activity. The investigators estimated that more than 500,000 metric tons of grain has been shipped by Russia from Ukrainian ports. The theft that ISRP identified is the tip of a very large iceberg. Their report stated:

Russia has taken as much as 11,000 metric tons of Ukrainian metal products from the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works and Ilyich Iron and Steel Works plants in Mariupol, mostly hot-rolled steel. A minimum of another 28,000 metric tons has been loaded onto ships that are currently moored in the port of Mariupol. Another 195,000 metric tons of metal products produced by Azovstal and Ilyich Iron and Steel Works also remain in the port, inaccessible to the producers or to legal buyers.

The investigators now believe that in addition to the steel itself, Russia is planning – or has already begun – to steal sophisticated equipment that will eventually be used by Russian steel makers, which are still permitted to sell semi-finished steel products into the lucrative European market and will undoubtedly benefit from the destruction of their Ukrainian competitors.

We will get to the story of this equipment theft below, but, first, it is important to understand the extent of the looting that began shortly after Russia invaded in February and how that theft is carried out.

A favorite piracy technique is transshipment, in which a bulk carrier anchors in a port – often the Kavkaz South Anchorage at the southern end of the Kerch Strait, the heavily traveled passage between the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea – and is met by a general cargo ship that has made an illegal entry at a Ukrainian port for purposes of loading looted grain. While transshipment is not per se illegal, its strategic advantages have been cynically exploited by Russian grain exporters to increase their profits. According to the ISRP report:

Transshipment can make it harder to track the stolen goods using ship data, as the ship that loaded the stolen cargo does not bring that cargo to another port for unloading. This method can also allow smaller, faster ships that may be able to enter and exit shallower ports or ports partially blocked by debris or mines to carry out multiple, smaller loads that can then be transferred to larger ships, which can also receive stolen cargo from multiple ships and even multiple ports.

Because grain leaving a Russian port, regardless of its initial provenance, may be labeled as of Russian origin, transshipment provides the perfect opportunity for dishonest exporters to sell smuggled grain to unsuspecting customers.

In many of the cases currently being investigated by ISRP, a cargo ship will leave the Russian port of Azov with cargo loaded at a grain terminal there. That grain is first delivered to a larger ship waiting in the Kerch Strait before the general cargo ship, rather than returning to Azov, enters a Ukrainian port to take on a cargo of stolen grain. The stolen grain is mixed with grain shipped from a Russian port, when it is loaded onto the bulk carrier in a Russian port, allowing the entire cargo to be re-labeled as of Russian origin, so the exporters can avoid trade sanctions on stolen Ukrainian grain.

ISRP researchers identified and listed in the report 21 instances of “suspected illegal exports of Ukrainian resources,” along with the names of ships, their routes, and the estimated quantities aboard. The vast majority of the ships identified at the time the report was written landed in Turkish ports. Stolen grain was also shipped to Syria or directly to Russia. What happens to the grain after that is harder to say, but evidence points strongly toward either direct sales by Russia and state-sanctioned Russian companies, earning funds to continue the prosecution of Russia’s war on Ukraine, or storage for later distribution by Syria or Russia.

“The brazen nature of its crimes,” says the report, “makes it clear that Russia has no intent to make the owners of the stolen resources whole and showcases the characteristic depravity of Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine.” Of special concern is the participation of Turkey, a NATO country.

The report also states:

The theft and destruction of hundreds of thousands of tons of grain and other agricultural products will only add to the casualties of this war and spill over to the many countries that rely on Ukrainian grain. The theft of Ukrainian steel will provide Russia with the means to maintain its troops, weapons and supplies and prolong the war either directly or through the sale, along with the stolen grain, to other states or private actors.

Looting clearly violates international law. Article 33 of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War prohibits pillaging. Article 53 prohibits the destruction of private property except where “rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.” Article 55 declares that an occupying force “may not requisition foodstuffs … except for the use by the occupation forces and administrative personnel, and then only if the requirements of the civilian population have been taken into account.” Further, Article 55 requires that, subject to other international agreements, the occupying force must “make arrangements to ensure fair value is paid for any requisitioned goods.”

A Humanitarian Corridor at the Same Time Grain Is Being Stolen?

Even as stolen Ukrainian grain is sold in Turkish ports, Turkey has been intimately involved in United Nations negotiations to allow Ukrainian grain to be exported for humanitarian aid. Under this Black Sea Grain Initiative, Russian, Ukrainian, Turkish and UN officials formed a Joint Coordination Center in Istanbul to provide a humanitarian corridor through the Black Sea for Ukrainian grain and fertilizer via Odessa, Chornomorsk and Pivdennyi to alleviate food shortages around the world, including those caused by Russian destruction and theft.

The arrangement was delayed in part by a July 23 Russian attack on Odessa’s seaport with “cruise missiles hours after signing a deal to unblock Ukrainian grain exports from three Black Sea ports, including Odessa.” A week later, in another attack, the Russians killed the owner of a large Ukrainian grain producer and exporter, Oleskiy Vadatursky and his wife in the city of Mykolaiv.

Is the deal anything more than a cynical Russian ploy? This remains to be seen, but it is doubtful that helping Ukraine distribute its grain to the world is an item high on the Russian agenda. Whatever Russia’s motives, Turkey must end the assistance it is giving to Russia’s piracy campaign – and the UN should demand that the looting end and that Russia compensate Ukrainians for the theft of their resources.

Already, the Russians are using misinformation to exploit the humanitarian grain corridor. According to Polygraph.Info, the fact-checking arm of Voice of America, the state-owned Russian news channel RT (Russia Today) on Sept. 1 claimed that “Ukraine’s ‘hunger relief’ for Africa goes to rich countries instead.”

In a video clip posted to Twitter, the RT narrator argues: “Why did all of East Africa only get one ship if they are so desperate for food? U.N. records show that Ukrainian grain went to other places as well: Ireland, Greece, Italy – countries that are not exactly hunger stricken. Well, Ukrainian officials wipe their hands clean of that since after all, the free market decides.”

The first shipment of Ukrainian grain to support operations of the U.N.’s World Food Program (WFP) in the Horn of Africa left Pivdennyi aboard the U.N.-chartered Brave Commander on August 16. That shipment of 23,300 tons of wheat arrived in Djibouti on August 30. Another ship, the Sea Eagle, is headed to Sudan with 65,340 tons of wheat, while the Karteria is bound for Yemen with 37,500 tons of grain and the Massa J is carrying 28,500 tons of wheat to Somalia.

Our subsequent search of the Joint Coordination Center’s website found that a shipment to Djibouti departed on August 21, one to Yemen left on Sept. 3, and to Somalia on Sept. 7. A shipment from Odessa to Kenya is anticipated but with no definite date.

Then in a speech in Vladivostok on Sept. 7, Vladimir Putin himself took up the theme, saying that Moscow will “have to think about changing routes” for Ukrainian grain shipments because they weren’t reaching poorer countries.

U.S. officials have cited the grain-export deal “to rebuff Kyiv’s insistence that Russia should be designated a ‘terrorist state,’ saying the designation would prevent the kind of exchanges that made that breakthrough,” according to a Reuters report.

While these shipments are welcome, they don’t come close to mitigating the damage that Russia has done to the people of Ukraine and the global economy. The World Food Program (WFP) estimates that “345 million people in more than 80 countries are facing acute food insecurity, while 50 million people in 45 countries are at risk of being pushed into famine.” The Polygraph article quotes WFP Executive Director David Beasley stating, “It will take more than grain ships out of Ukraine to stop world hunger, but with Ukrainian grain back on global markets we have a chance to stop this global food crisis from spiraling even further.”

As research by the ISRP and other organizations have revealed, Russia’s theft is keeping that grain from hungry global markets. According to Polygraph: “Reports indicate that Ukraine, one of world’s top exporters of grains, oils, and seeds, suffered more than $1 billion worth of losses to its agricultural sector since Russia launched a full-scale invasion.”

Ukraine Moves to Seize Ships

The Ukrainian government is not sitting on its hands. It is moving to seize ships engaged in, or associated with, the theft. On July 29, the Ukrainian embassy in Lebanon issued a statement that it suspects that 10,000 tons of flour and barley aboard a Syrian state-owned ship docked in Lebanon’s Tripoli had been stolen from Ukraine. The statement came as a Ukrainian court issued an order to seize the ship along with its cargo. At last report, Lebanese authorities were investigating.

The Ukrainian embassy in Lebanon stated that during Russia’s occupation more than 500,000 tons of grain has been “stolen from occupied Kherson, Zaporizhia and Mykolaiv region” and that “attempts to transport most of these grains to Middle Eastern countries, including Egypt, Turkey and Syria, and attempts to transfer them to Lebanon were recorded.”

According to a report in the Lebanese media outlet Naharnet, the embassy “noted that the facts of illegal exportation of grain from Ukraine were confirmed not only by law enforcement agencies, but also within the framework of journalistic investigations.”

The embassy’s statement referred to ISRP’s July report, which identified the Laodicea, the ship that was cited in the court’s order. As stated in ISRP’s August 1 press release, Laodicea’s route was “consistent with data collected by ISRP investigators that have been tracking Laodicea, along with dozens of other ships.”

The Voyages of Two Ships Named Emmakris

Another ship, identified by a CNN source as the Emmakris III, was also detained by Ukrainian authorities after a court ruling in Kyiv. The ship, owned by a Russian company, had been loaded with grain at the Black Sea port of Choromorsk. As of Sept. 6, it was still being detained, according to Reuters.

The CNN report, published July 29, contained details similar to those discovered by the ISRP in its investigations of numerous other ships. CNN stated that the “prosecution in the Kyiv court case said that while the Emmakris III is ostensibly owned by a company in Dubai, its ‘actual owner’ is a Russian shipping firm based in Rostov-on-Don called Linter.” The CNN report continued:

Linter is also listed by shipping databases as the owner of the Emmakris II, which has allegedly been involved in carrying grain stolen from occupied parts of Ukraine. Linter’s website includes photographs of the Emmakris II in the Black Sea. A weeks-long investigation by CNN based on satellite imagery, photographs and shipping data, shows that the Emmakris II spent several days moored off the port of Sevastopol in Russian-annexed Crimea at the end of June.

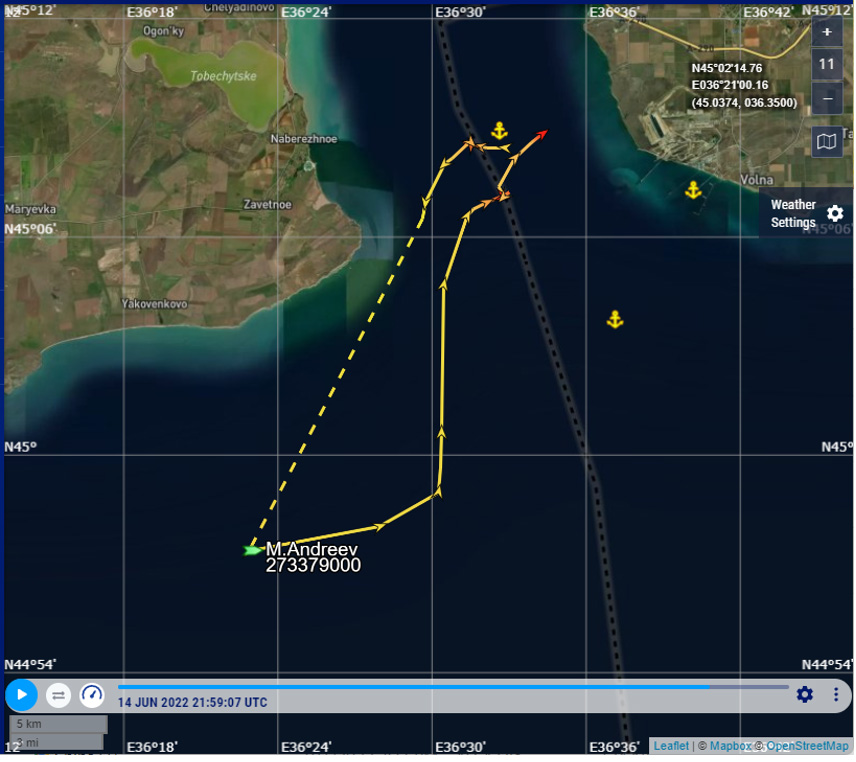

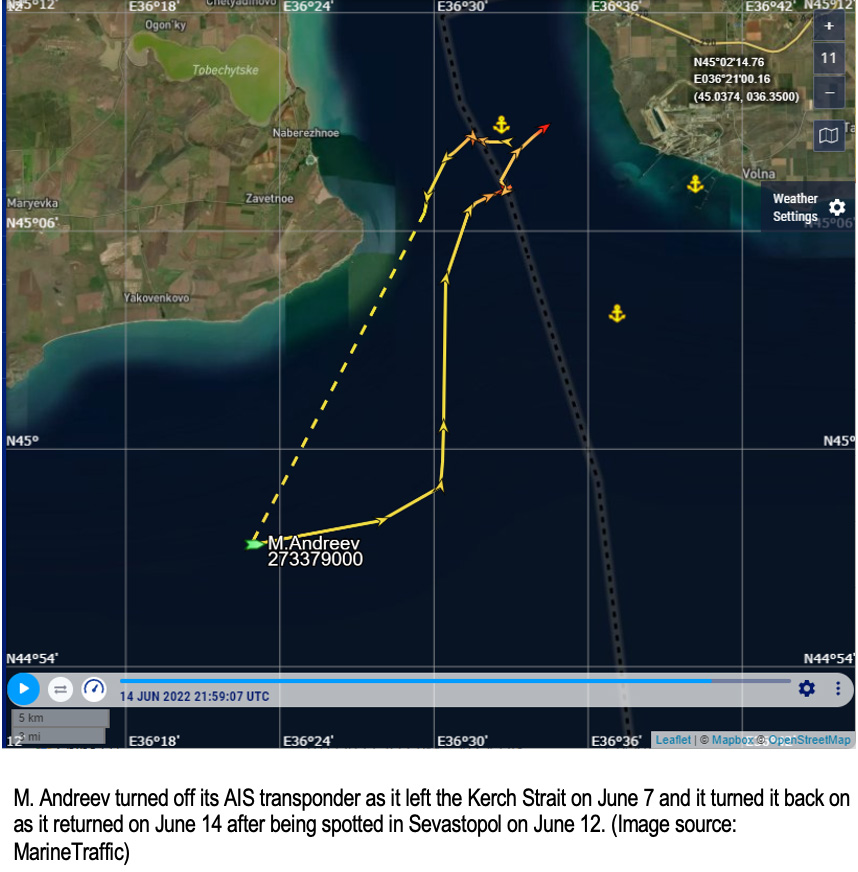

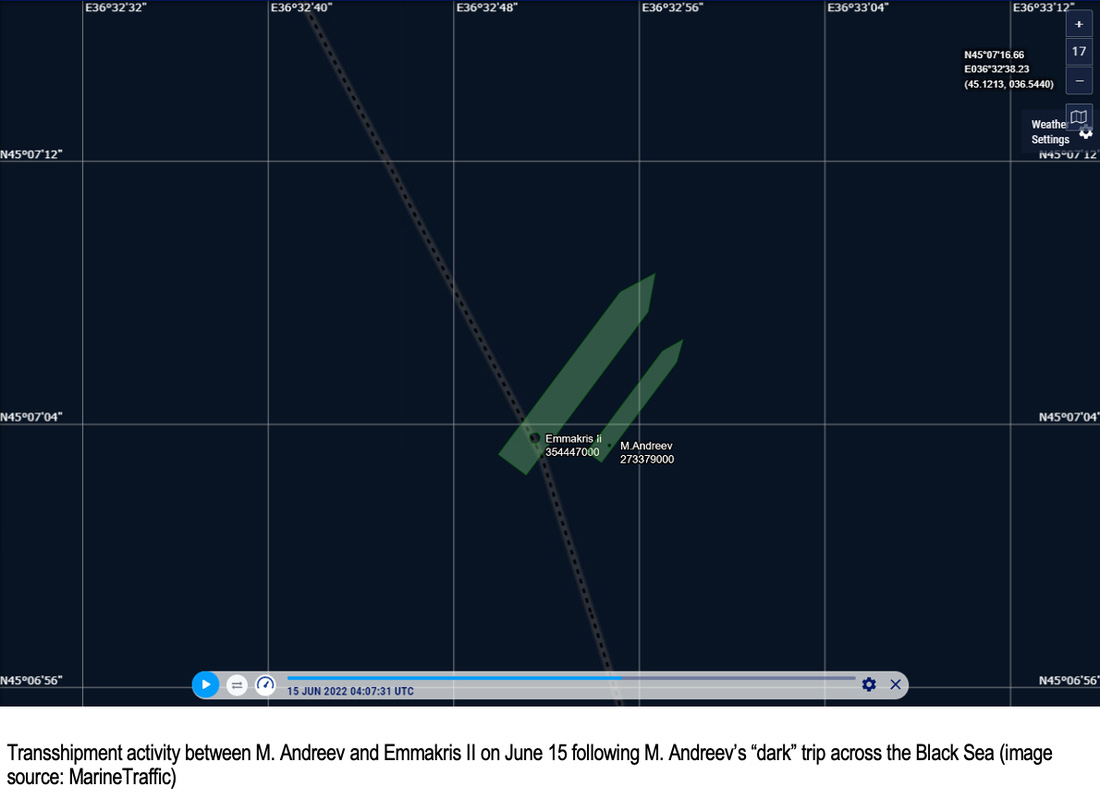

Then, in a pattern of transshipment cited in other cases by the ISRP report, the Emmakris II, said CNN, “received several visits from a smaller ship that had loaded grain in the port – and which appears to have transferred its cargo to the Emmakris II. The smaller vessel, the M Andreev, which is also registered to Linter, had been photographed loading in Sevastopol days before it went alongside the Emmakris II, according to a shipping source in Sevastopol.”

[Ship registry information available from MarineTraffic, Shipping Explorer, and Baltic Shipping show M Aandreev as registered to Don River Shipping JSC of Rostov-on-Don, Rostov, Russia. ISRP investigators have not been able to independently connect Don Rive Shipping to Linter LLC at the time of this publication.]

The ISRP report noted the transfer of cargo in the Kerch Strait on June 25 from M Andreev to Emmakris II. ISRP investigators have identified multiple incidents of stolen grain being transferred by M. Andreev and others onto Emmakris II for transshipment.

CNN reported on the theft of Ukrainian grain back in May in an article with the headline, “Russian ships carrying stolen Ukrainian grain turned away from Mediterranean ports – but not all of them.” That report focused on the bulk carrier Matros Pozynich. This ship, like many identified in the theft of Ukrainian grain, departed from the port of Sevastopol in Russian-occupied Crimea. As CNN stated:

Crimea, annexed by Russia in 2014, produces little wheat because of a lack of irrigation. But the Ukrainian regions to its north, occupied by Russian forces since early March, produce millions of tons of grain every year. Ukrainian officials say thousands of tons are now being trucked into Crimea.

Kateryna Yaresko, a journalist with the SeaKrime project of the Ukrainian online publication Myrotvorets, told CNN the project had noticed a sharp increase in grain exports from Sevastopol – to about 100,000 tons in both March and April.

In a description of Matros Posynich’s travels after the CNN report, ISRP investigators identified the ship as departing Sevastopol with an intended destination of Beirut. Instead, on June 17, the ship turned off its AIS “while approximately 25 kilometers from Tartus,” in Syria. There is no recorded call at Beirut. Five days later, the ship turned its AIS back on in the same position. The investigators suspect that Syria was the actual destination for the grain.

ISRP continues to investigate the transit of grain to Syria, which has essentially become a Russian protectorate, and its disposition afterwards.

Stealing Equipment to Manufacture Valuable Steel

Meanwhile, the ISRP on Aug. 30 issued a press release stating it had “determined there is a high probability Russia is in the process of stealing sophisticated equipment from two steel plants in Ukraine and shipping it to its own manufacturers to improve Russia’s sales to Europe and elsewhere.”

According to ISRP’s chief spokesperson, retired U.S. Ambassador James K. Glassman, “Russia’s own steel plants are largely antiquated, but through the illegal theft of advanced equipment made expressly for the Avozstal and Ilyich factories in Mariupol, Russia can boost its position as an exporter of semi-finished steel to Europe.”

Three weeks after the invasion of Ukraine, the European Union banned imports of Russian finished steel products, but the EU continues to permit imports of semi-finished products, such as slab and cast iron. Russia would benefit enormously from the theft of unique and valuable equipment developed as part of a modernization at the plants.

In April, as though signaling his intentions ahead of time, Vladimir Putin declared that improving steel production was a high priority, but sanctions currently prevent Russia from acquiring such equipment from the EU and the US. “We must make changes to the structure of production and the supply of Russian metallurgical products,” he said, calling for an expansion in industrial capability and the range of products Russia produces.

While ISRP cannot, with absolute certainty, confirm that theft of steel-making equipment from Ukraine has occurred yet, Peter Andrushchenko, senior adviser to the mayor of Mariupol, stated on August 19 that Russian occupiers had begun to cut into scrap metal and dismantle equipment at the Ilyich Iron and Steel Works in Mariupol. These actions certainly indicate that the removal of this equipment and its shipment to Russian plants is at least imminent.

The destruction of the steel plants, with estimated costs of $10 billion, has certainly benefited Russia already by removing Ukraine, until the invasion one of the top steel producers in the world, as a major competitor.

“What would really help,” said Glassman in the press release, “is a full-on ban of all Russian steel products – finished and semi-finished – not just by the EU but by countries such as Turkey. By purchasing Russian steel, these nations are aiding in Russia’s war on Ukraine – and prolonging the terrible suffering. Now, with Russia likely to be making that steel with Ukrainian equipment, the shame and complicity are compounded.”